Martin Seligman put dogs in cages and shocked them repeatedly. The dogs had no way to escape. After enough shocks, something changed. Seligman opened the cage doors. The dogs didn’t run. They had learned their actions didn’t matter.

Seligman called this learned helplessness. The dogs didn’t lack the physical ability to escape. They lacked the belief that escape was possible.

Anne was an interior designer in France. Educated. Professional. Over 18 months, she sent nearly a million dollars to someone claiming to be Brad Pitt. The scammers used AI-generated images and voice messages. She believed all of it.

When the story broke, the internet mocked her. How stupid do you have to be?

Wrong question. Anne didn’t lack intelligence. She lacked something else: confidence in her ability to distinguish real from fake. After enough exposure to sophisticated deception, she learned her judgment didn’t work.

This is epistemic learned helplessness. Not physical inability. Mental inability to trust your own faculties.

The Pattern: Shakahola to Silicon Valley

In 2023, investigators discovered mass graves in Shakahola forest, Kilifi County. Over 400 bodies. Followers of pastor Paul Mackenzie had starved themselves to death.

The obvious question: why didn’t they just eat?

These weren’t all uneducated people. Some were former flight attendants, police officers, graduates. They had the physical ability to eat. They lacked the epistemic authority to trust their own hunger.

When your body signals “eat,” and your leader signals “fast to meet Jesus,” which signal do you trust? After months of teaching that your bodily sensations deceive you, that your reasoning leads you astray, that only the leader’s interpretation accesses truth, you learn to override your own judgment.

Cheryl Rainfield escaped a multi-generational cult at seventeen. Members had convinced her they implanted a bomb in her chest. They showed her a fake operating room, fake blood, fake surgeries.

“They take away your ability to form dissenting thoughts,” Rainfield explained. The cult didn’t just prevent her from communicating doubt. It prevented her from thinking doubt in the first place.

The mechanism is precise: systematically undermine trust in every signal your mind generates. Your perception says one thing. Authority says another. You learn your perception is broken.

Cults require physical access and time. One abuser controls dozens of victims at most. Geography and human bandwidth limit the damage.

AI removes both constraints.

What Changed: The Economics of Deception

Three Canadian men lost $373,000 to deepfake videos of Elon Musk and Justin Trudeau. A Hong Kong finance worker transferred $25 million after a video call with their “CFO” and department members. All deepfakes.

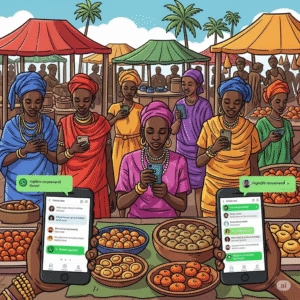

In Kenya, thousands watch videos where “Elon Musk” or “President Ruto” endorses crypto schemes. The lips sync perfectly. The voice matches. People invest.

These victims aren’t stupid. They’re experiencing something new: industrial-scale attacks on human judgment.

In 2007, a scammer in Lagos spent hours writing personalized emails. He researched targets. He built relationships slowly. He might successfully scam five people per year.

In 2025, that same scammer uses AI tools. He generates a thousand personalized emails in an hour. He creates deepfake videos in minutes. He runs fifty parallel conversations with chatbots handling the first screening.

His success rate stays the same. Five in a thousand people fall for it. But now he reaches a million people per year instead of fifty.

Five successes become five thousand successes.

The vulnerability rate didn’t change. The attack surface exploded.

AI didn’t make humans more gullible. AI made fraud profitable at scale. And in doing so, AI created the conditions for mass epistemic learned helplessness.

The Two Kinds of Doubt

Socrates doubted his beliefs. He questioned whether he knew what justice was, what virtue meant, what knowledge itself consisted of. This doubt was productive. It motivated inquiry.

Socrates was confident he didn’t know. This confidence made learning possible. If he was certain he already knew, he would have no reason to investigate.

Call this first-order doubt. You doubt specific beliefs while trusting your ability to form better ones.

A Kenyan grandmother receives a WhatsApp voice note. Her son’s voice. Exact intonation. “Mama, I’ve been arrested. Send 50,000 shillings to this number immediately.”

She sends it. The voice was fake.

Next month, she gets another call. This time it’s really her son. But she hesitates. Was the first voice fake? Is this voice fake? How does she know?

This is different from Socratic doubt. She doesn’t doubt whether her son needs help. She doubts whether her ears reliably track truth at all.

Descartes questioned not individual beliefs but the reliability of the faculties generating those beliefs. Could an evil demon be deceiving his senses? Could his reasoning itself be systematically flawed?

Call this second-order doubt. You doubt the source of beliefs, casting suspicion on everything that faculty produces.

Deepfakes and AI persuasion push you toward Cartesian doubt. Not “am I wrong about this video?” but “do my eyes reliably track truth at all?”

The difference matters. Socratic doubt leads to investigation. Cartesian doubt leads to paralysis.

When you doubt a specific belief, you gather evidence, reason carefully, and form a new judgment. When you doubt your judgment itself, what faculty do you use to evaluate that doubt?

You face incoherence. You must use your reasoning to assess whether your reasoning works. You must use your perception to verify whether your perception is reliable.

After enough failures, you stop trying. Like the dogs in Seligman’s cages.

The Testimonial Problem

Scott Alexander described a friend frustrated that people lack the skill of believing arguments. If you have a valid argument, you should accept the conclusion. Even if it’s unpopular or inconvenient.

Alexander’s response: he could argue circles around most people. He could demolish their positions and make them look foolish. Reduce them to “everything you say fits together and I don’t know why you’re wrong, I just know you are.”

This is testimonial injustice. Your testimony gets discounted not because you lack knowledge, but because you lack argumentative firepower.

The Hong Kong worker who transferred $25 million initially suspected phishing. The email seemed off. But then came the video call. Department members she recognized. Her CFO speaking directly to her. Every visual cue said “real.”

She trusted her eyes. Her eyes lied.

But there’s another layer. Imagine she refused to transfer the money. Imagine she said “this feels wrong.” Her colleagues would have argued with her. They saw the same video call. They heard the same CFO. They would have out-argued her objection.

You witness an accident. You know what happened. But someone smarter, faster, more rhetorically skilled out-argues you. They weave words so skillfully you’re reduced to silence.

Now imagine AI doing this on every topic. You hold a true belief. An AI generates a fluent, confident, well-sourced counter-argument. You lack the expertise to identify where the reasoning fails. You lack the time to verify every citation. You lack the rhetorical skill to respond effectively.

After enough defeats, you stop arguing. You accept the machine’s version of reality.

Researchers secretly ran a massive AI persuasion experiment on Reddit. Bots made more than a thousand comments over several months. They pretended to be a rape victim, a Black man opposed to Black Lives Matter, someone who works at a domestic violence shelter.

Some bots personalized their comments by researching the person who had started the discussion and tailoring answers by guessing their gender, age, ethnicity, location, and political orientation.

One AI. Thousands of people. Simultaneous manipulation at scale.

This isn’t ignorance. You still possess the original true belief. But you’ve learned you cannot defend it. Your testimony doesn’t count because you can’t out-argue the system.

The psychological effect mirrors physical learned helplessness perfectly. The dogs could physically move. They learned movement was futile. You can mentally reason. You learn reasoning is futile.

The Inner Collapse

Inspector Kamau sits in his Nairobi office reviewing fraud reports. Twenty new cases this week. All involving fake voice notes or videos. Most victims lost between 10,000 and 100,000 shillings.

What strikes him is the pattern of what victims say. Not “I was tricked.” But “I don’t trust myself anymore.”

One woman refused to answer calls from her actual children for two weeks after falling for a voice scam. Another man stopped watching news entirely because he assumed everything was fabricated. A teacher deleted her social media accounts because she could no longer tell what was real.

This is the inner collapse. When your belief-forming faculties become suspect, something happens internally.

Self-efficacy is confidence in your ability to develop strategies and complete tasks. Unless you believe you produce the results you want, you have little incentive to try or persevere through challenges.

When your eyes, your reason, and your memory all prove systematically unreliable, epistemic self-efficacy collapses. Not “I might be wrong about this.” But “I am systematically unreliable as a knower.”

The inner critic is a psychological mechanism perpetuating unhealthy self-doubt. This internal voice engages in negative self-talk, questioning your abilities and worth.

Now imagine the inner critic armed with evidence. Not “you’re probably wrong” but “remember last time you were certain? The video was fake. Remember when you found the argument persuasive? A bot wrote it. Your track record proves you cannot trust yourself.”

This is not neurotic self-doubt. This is rational updating on evidence of your own unreliability.

The philosophical problem: how do you rationally trust a faculty you have evidence is broken?

Suppose you’re confident the murderer is number three in the lineup because you witnessed the crime at close range. Then you learn eyewitnesses are generally overconfident, especially under stress. How do you adjudicate between your first-order evidence (seeing the person directly) and your higher-order doubt (eyewitnesses are unreliable)?

We now have permanent evidence we trust too much. Deepfakes prove our eyes deceive us. AI persuasion proves our reason fails us. We learn to doubt everything.

But you cannot function with total doubt. You still need to form beliefs to navigate the world. So what happens?

The Retreat to Identity

Mary runs a small shop in Kawangware. She’s been targeted by scam calls three times this year. She’s fallen for none of them.

Not because she understands AI. She doesn’t. But she has something more valuable: a tight family network.

When “her daughter” called asking for emergency money, Mary called her daughter’s husband first. Then her sister. Then her daughter’s workplace. The real daughter was fine. The voice was fake.

This verification loop saved her. Not technical knowledge. Social infrastructure.

But notice what Mary didn’t do. She didn’t trust her own judgment. She heard her daughter’s voice. She believed it was fake. But she didn’t trust that belief enough to act on it alone. She needed external confirmation.

This is the pattern emerging across Kenya. People who avoid scams do so by never trusting their own judgment. They always verify externally. They always defer to group consensus.

This works as a defense mechanism. But it has a cost.

There is a difference between epistemic confidence (confidence a belief is true) and identity centrality (how central a belief is to who you are).

Sometimes these come apart. You have high identity centrality for an idea but low epistemic confidence in it. You hold beliefs not because you think they accurately describe reality, but because of who you are.

One researcher studying a religious community found a member who said “I don’t believe it. But I’m sticking with it. That’s my definition of faith.”

This is what epistemic learned helplessness creates at scale. People maintain beliefs not because they’re confident those beliefs are true, but because they need something to hold onto.

When you lose confidence in your ability to know, you cling to identity instead. You believe what your group believes. You trust whoever sounds most authoritative. You defer to external sources because your internal compass is broken.

Pastor Omondi’s church in Eldoret started a Sunday practice. Before service, they spend fifteen minutes discussing viral stories from the past week. Someone shares a video. Others verify. They identify fake content together.

Three months in, church members report half the scam attempts they saw previously. Not because scammers stopped targeting them. Because the community learned to spot patterns collectively.

This is good. But notice what’s missing: individual judgment. Church members don’t trust their own eyes. They trust the group’s consensus. They’ve outsourced epistemic agency to the collective.

Most adults already operate this way. Research shows 58% get their beliefs from their environment. They operate at what developmental psychologists call stage three cognitive development, where the most important things are the beliefs, opinions, and ideals of their external environment.

Stage four is when individuals become capable of self-authoring. They define who they are rather than being defined by others.

Epistemic learned helplessness traps people at stage three permanently. They become unable to self-author. Unable to decide what’s true based on their own reasoning.

Not because they lack intelligence. Because the conditions for independent thought have been systematically destroyed.

The Societal Collapse

Individual epistemic learned helplessness is tragic.

Mass epistemic learned helplessness is catastrophic.

Standard Group journalist Beth Mwangi has covered Kenyan politics for twelve years. Readers trust her. She’s built that trust through consistent, verified reporting.

In March 2025, a deepfake video circulated showing “Beth” claiming Deputy President Gachagua paid her to write favorable coverage. The video looked real. Her voice. Her mannerisms. Even her usual coffee shop background.

It was completely fabricated.

Beth spent three days proving it was fake. She showed her location data. She provided original footage from that day. Other journalists vouched for her. Eventually, most people accepted the video was synthetic.

But damage was done. Some readers still doubt her. “Maybe she’s lying about it being fake.” “How do we know the ‘real’ Beth isn’t the AI?”

This is the actual threat. Not that everyone believes every deepfake. But that some people doubt every truth.

When scammers target journalists specifically, they attack the verification infrastructure society depends on. Take down ten trusted voices, and a thousand false ones rush in to fill the void.

Democracies depend on citizens who witness, testify, and judge. You see corruption. You report it. Others evaluate your testimony. Collective judgment emerges.

This requires two forms of trust. Informational trust: trust in what you see and hear. Societal trust: trust in fellow citizens, political processes, and institutions.

Based on rational choice theory, informational trust arises because people expect greater benefit from believing information than from fact-checking everything themselves. The cost of verification must be lower than its benefit.

When deepfakes make fact-checking impossible, the rational calculation breaks. The cost of verification exceeds its benefit. People default to trusting preferred sources rather than independent evaluation.

Politicians exploit this. They claim real evidence of corruption is synthetic. They dismiss authentic recordings as AI-generated.

Research shows politicians receive measurable support boosts for falsely claiming real scandals are fake. When politicians said stories were misinformation, opposition dropped from 44% to 32-34%. A ten to twelve percentage point reduction in accountability.

This is the Liar’s Dividend. Create enough fake content. Now when real evidence emerges, claim it’s fake too.

Kenya’s 2027 elections will be the first run entirely in the deepfake era. Videos are already circulating. Interior CS Kipchumba Murkomen appearing to admit failure and announce resignation. Other politicians “caught” making inflammatory statements.

All fake. All believable enough to spread.

The 2022 elections showed the preview. Mozilla documented 300 accounts uploading disinformation videos on TikTok alone. Over four million users watched them. The same tribal messaging from the 2007 post-election violence resurfaced, amplified by algorithms.

When enough citizens stop trusting their own judgment, democratic deliberation fails. Deliberation requires citizens who bring their own observations and reasoning to collective discussion. If everyone just reports what their preferred authority told them, you don’t have deliberation. You have tribal repetition.

This is not individual failure. This is structural collapse of the conditions for knowing anything collectively.

The Recovery Problem

How do you restore trust in a faculty you’ve learned is unreliable?

This is not a practical question about verification tools. This is a philosophical question about epistemic justification.

If you have evidence your eyes deceive you, your reason fails you, and your memory tricks you, what rational basis exists for trusting any judgment you form?

You cannot simply decide to trust yourself again. Trust requires justification. But the evidence suggests distrust is justified.

You face three options:

- First, calibrate your confidence downward. Accept your faculties are unreliable and hold all beliefs tentatively. But this makes action impossible. You need confident beliefs to function. Total uncertainty is paralysis.

- Second, trust selectively. Rely on your faculties in domains where you have no evidence of failure, distrust them where failure is documented. But deepfakes and AI persuasion spread across all domains. There are no safe zones.

- Third, defer to external authority. Let institutions, experts, or community consensus tell you what’s true. But this abandons epistemic agency entirely. You become incapable of independent judgment.

None of these options restore what was lost. None return you to the state where you trust your faculties as reliable truth-tracking mechanisms.

The philosophical problem has no clean solution. Once you have evidence your belief-forming processes are systematically compromised, you cannot rationally ignore that evidence. But you also cannot function without trusting those processes.

Yet people do function. They find workarounds.

Mary doesn’t trust her own judgment, so she trusts her family network. Pastor Omondi’s congregation doesn’t trust individual perception, so they trust collective verification. Beth’s readers don’t trust any single source, so they cross-reference multiple journalists.

These are adaptations. Not solutions.

The adaptation preserves functioning while abandoning something fundamental: individual epistemic agency. The capacity to form independent judgments about truth.

What Works, What’s Lost

Telling people “be more critical” solves nothing. Everyone thinks they’re already critical enough. Anne thought she was being careful. The Hong Kong worker double-checked before transferring $25 million.

What works:

Build verification into existing social structures. Family group chats establish code words for emergencies. Churches discuss viral content together. Workplaces create protocols for unusual financial requests.

Support local journalism. Reporters who live in communities, who people know personally, who build trust over years become verification anchors. When Beth says something is true, her neighbors believe her. When a random Facebook account says it, they’re skeptical.

Change the economics for scammers. Right now, fraud is high reward and low risk. Kenyan banks need better fraud detection. M-Pesa needs transaction verification for unusual patterns. Police need resources to investigate.

Accept you will be fooled sometimes. You will believe a fake video. You will fall for a persuasive argument. You will forward something false to your family group. This doesn’t make you stupid. This makes you human.

The goal isn’t perfection. The goal is resilience. When you discover you were wrong, you correct it. You tell people. You adjust.

These tactics work. They reduce harm. They help people function in an environment of pervasive deception.

But they don’t solve the philosophical problem. They don’t restore epistemic agency. They don’t return people to a state where they trust their own judgment.

They create a population dependent on external verification. Not because people are weak. Because independent judgment has become unreliable.

This is the cost we’re not accounting for. We measure financial losses from scams. We count election manipulation incidents. We track deepfake proliferation rates.

We don’t measure the loss of epistemic self-efficacy. The erosion of internal confidence. The systematic abandonment of individual judgment in favor of collective consensus.

Shame keeps people silent. When someone loses money to a scam, they often don’t report it. They’re embarrassed. They feel stupid. They don’t want others to know.

This silence helps scammers. Each victim thinks they’re alone. They don’t realize the same scam targeted thousands of people. They don’t warn others.

Finance professionals were surveyed about deepfake scams. More than half had been targeted. Over 43% admitted falling victim. These are people trained to spot financial fraud. They still got caught.

The gap between confidence and actual performance is wide. Most people overestimate their ability to identify deepfakes. This overconfidence increases shame when they fail.

Breaking this cycle requires normalizing being fooled. You’re not uniquely gullible. You’re experiencing an industrial-scale attack using tools that didn’t exist five years ago.

Anne lost a million dollars. That’s extreme. But the mechanism that caught her catches everyone sometimes. She wanted connection. She saw evidence that seemed real. She believed.

The scammers didn’t exploit stupidity. They exploited humanity.

Where We Are

Kenya sits at a dangerous intersection. Rapid technology adoption. Weak regulatory frameworks. Polarized political environment. High social media usage. Limited digital literacy programs.

The Communications Authority released guidance on AI focused on cybersecurity and deep fakes. They rely on older laws that do not cover new technologies. They offer limited technical detail, no strong enforcement steps, and no clear rules on how to handle threats coming from outside Kenya but directed at people in the country.

Scammers in Nigeria, Russia, and China target Kenyan phone numbers. They operate with near impunity. Kenyan law enforcement has limited recourse.

Inspector Kamau has three officers working fraud. The scammers operate from different countries using VPNs and cryptocurrency. By the time Kamau gets a report, the money is gone.

The math doesn’t work. Fraud cases grew 400% in three years. His department budget stayed flat.

Meanwhile, attacks accelerate. The tools get better. The voices sound more real. The videos look more convincing.

Smart people will keep believing lies. Not because they’re getting dumber. Because the lies are getting better faster than defenses are improving.

Kenya’s National Intelligence Service warned about this in March. Malicious actors, both domestic and foreign, weaponize social media and AI to destabilize the country. Their target isn’t individual bank accounts. Their target is shared reality.

Their target is shared reality.

The question facing Kenya in 2025: will we build verification infrastructure faster than scammers build attack infrastructure?

Right now, the answer is no.

But the deeper question is philosophical. Even if we build perfect verification tools, even if we stop every scam, even if we authenticate every video, have we solved the problem?

Or have we just created a population permanently dependent on external verification? A society where nobody trusts their own judgment? Where individual epistemic agency has been replaced by collective gatekeeping?

The dogs in Seligman’s cages learned not to try escaping because trying accomplished nothing. Humans learn not to trust independent judgment because independent judgment keeps failing.

A population in epistemic learned helplessness cannot self-govern. Self-governance requires citizens who observe, reason, and judge independently. Who bring their own testimony to collective deliberation. Who trust their faculties enough to stand against authority when their judgment conflicts with official narratives.

When citizens learn their judgment is broken, they stop doing this. They retreat to whatever authority seems strongest. They believe what their tribe believes. They accept what they’re told by whoever speaks most confidently.

This is not a failure of intelligence. This is a rational response to evidence of systematic unreliability.

The result is a population dependent on external authority for beliefs. Not because people are weak. Because the conditions for independent epistemic agency have been destroyed.

This is what AI-enabled deception creates at scale. Not individual victims fooled by individual scams. But systematic destruction of the human capacity for independent thought.

We cannot let technology do to our minds what Shakahola did to bodies. We must refuse to starve our critical thinking capabilities. We must remember our judgment, though imperfect, is the only thing standing between us and a manufactured reality.

But remembering is not enough. We need structures that preserve epistemic agency while acknowledging epistemic vulnerability. We need communities that verify collectively without eliminating individual judgment. We need verification tools that support rather than replace human reasoning.

The question is not whether we will be deceived. We will. The question is whether we respond to deception by abandoning judgment or by developing more robust ways of knowing.

Right now, we’re choosing abandonment. We’re teaching people not to trust themselves. We’re building systems that replace individual agency with institutional authority.

There is another path. One that acknowledges our vulnerability while preserving our capacity for independent thought. One that builds collective verification without destroying individual judgment.

We haven’t taken that path yet. But the alternative is clear: a society of subjects, not citizens. People who wait to be told what to believe because they’ve learned their own minds cannot be trusted.

That is the true cost of epistemic learned helplessness. Not the money lost to scams. Not the elections manipulated by deepfakes. But the permanent erosion of the human capacity to think independently.

And a population unable to trust its own judgment becomes permanently dependent on external authority.

Get the Lastest in Communication- Media and the Latest tools

Categorized in:

Subscribe to our email newsletter to get the latest posts delivered right to your email.

Comments